Learn more about The Practical Side of Heaven

Copyright William C. Kiefert. All Rights Reserved.

Chapter Two, Part Fourteen: The Need for an Additional System of Logic

Those of us who make decisions in companies and industries like those mentioned above think of ourselves as good, “God-fearing” people. But does it really make sense to think that we can love God, if we do not love, or even care about, our neighbors? In his first letter, the apostle John expresses the relationship between loving God and loving our fellow man. “If a man say, I love God, and hateth his brother, he is a liar: for he that loveth not his brother whom he hath seen, how can he love God whom he hath not seen? And this commandment have we from him, That he who loveth God love his brother also.” (I John 4:20-21)

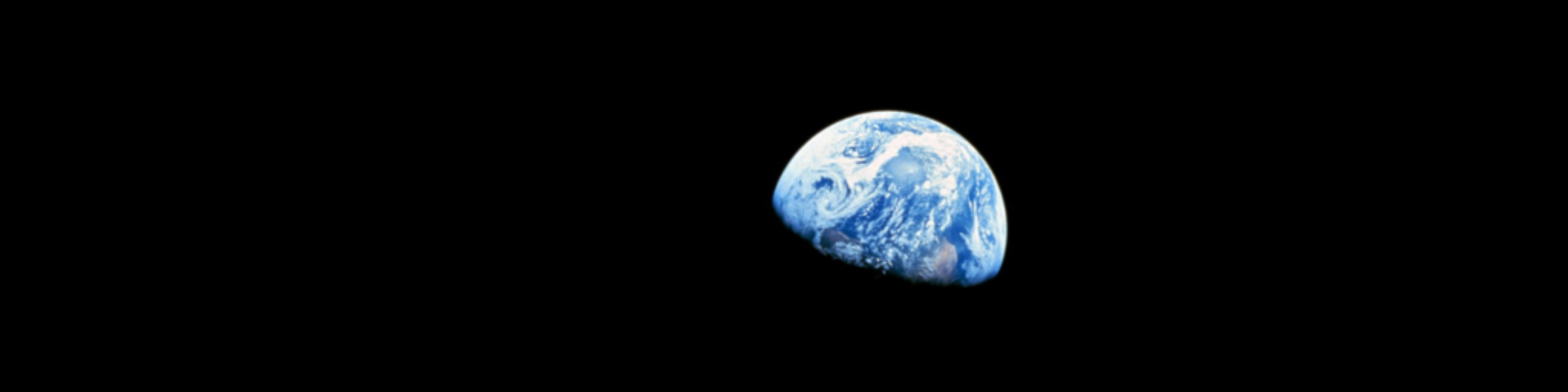

Martin Buber, in The Eclipse of God, describes what happens when we fail to love one another. We treat one another as a thing, an object, an It. To use poetic language, we might image ourselves as blocking out Love. Buber uses the metaphor of “an eclipse of God” to describe the condition. “What do we mean when we speak of an eclipse of God which is even now taking place? Through this metaphor we make the tremendous assumption that we can glance up to God with our “mind’s eye,” or rather being’s eye, as with our bodily eye to the sun, and that something can step between our existence and His as between the earth and the sun.” “In our age the I-It relation, gigantically swollen, has usurped, practically uncontested, the mastery and the rule. The I of this relation, an I that possesses all, succeeds with all, this I that is unable to say Thou, unable to meet a being essentially, is lord of the hour…. It steps in between and shuts us from the light of heaven.”

Those who reason in terms of a logic of either/or, us-versus-them, me-versus-you, feel justified in placing contaminated blood on the market for consumption. Rather than acting in love for the benefit of others and the good of the whole, they do only what is perceived to be in their own interest.

Many philosophers, psychologists, and theologians also recognize that our present rules for correct reasoning are questionable. Protestant theologian Paul Tillich (1886-1965) recognized that Aristotelian reasoning—which he called “technical…. [is] a kind of means—ends rationality that gives yes/no answers to either/or questions. It abolishes contradiction, cuts through anomaly, and permits vague anxieties to be replaced by definite fears which can supposedly be mastered. But, [for Tillich] the ethical, social, and existential issues of ultimate concern require a totally different kind of reasoning, a kind that encompasses several alternatives, and which answers not in terms of either/or, but of both/and. [He calls this reasoning] encompassing reason.” For example, we need to be both individuals and yet part of the society to which we belong; both rational and yet capable of deep feeling and passion; both loving and strong willed; and both innocent and yet capable of exercising power. When we use technical reason, where encompassing reason is more appropriate, we turn complex, multifaceted, and multi-dimensional issues into simplistic either/or choices, both of which may have negative consequences.

Biologist Jonas Salk expressed the need for a philosophy of reason which encompassed and reconciled both opposing alternatives of the Aristotelian either/or dichotomy. “We urgently need a philosophy of ‘both…and’ to qualify the present ‘either/or’. Once it was either our survival, or that of other species and natural elements, so we conquered, multiplied and subdued. Now we face an ego whose intellect, reason, objectivity, morality, differences, competitive nature, power and ‘win or lose’ psychology desperately needs a being whose intuition, feeling, subjectivity, realism, ability to differentiate, cooperate, and influence and reconciling powers can contain it.”

Anthropologist Ruth Benedict’s synergistic thinking goes beyond the either/or dichotomy in Aristotelian logic. Synergism is “the capacity of two forces, persons, or structures of information to optimize one another and achieve mutual enhancement.” Synergism holds in union and harmony what normally is taken to be opposite and irreconcilable.

From all comparative material, the conclusion emerges that societies, where non-aggression is conspicuous, have social orders in which the individual by the same act and at the same time serves his own advantage and that of the group. . . not because people are unselfish and put social obligations above personal desires, but when social arrangements make these identical.

Erich Fromm also called for synergistic thinking. Fromm “characterizes the productive personality as loving, caring, respectful, responsible and knowledgeable, and capable of holding in balance two opposing poles. On the other hand, masochistic loyalty and sadistic authority, destructive assertiveness and indifferent fairness are what characterize the non-productive personality in dealing with others.”

Abraham Maslow offers a similar analysis in terms of what he calls self-actualizing persons. Those of us who are not self-actualized find ourselves reasoning in the dichotomy of either/or choices. Self-actualized persons are those whose reasoning transcends this dichotomy.

Most Eastern religions question the credibility of the reasoning mind. They teach that “reasoning is less reliable as a guide to reality and truth than the direct perception and feeling of an individual properly prepared for spiritual receptiveness and subtlety by ascetic practices and years of obedient tutelage; that the purpose of knowledge and philosophy is not control of the world so much as release from it;…”

Those who criticize Aristotelian logic, then, are clear that humanity needs to learn how to transcend judgmental logic: to learn how to reconcile conflicting positive alternatives, to develop the capacity to encompass these alternatives in a dynamic whole and to build consensus rather than dissension. Stopping problems before they begin is the ultimate form of conflict resolution. Learning to apply either/or logic only when considering single nature classes is the means to this end. Creating a new system of both/and—nonjudgmental logic—which applies to multiple nature classes is the means to a new beginning. As psychologist Erich Fromm said, “Only when man succeeds in developing his reason and love further than he has done so far, only when he can build a world based on human solidarity and justice, only when he can feel rooted in the experience of universal brotherliness, will he have found a new, human form of rootedness, will he have transformed the world into a truly human home.”

As mentioned above, our knowledge of the world has led us to argue beyond Plato’s theory that a single nature alone is adequate to appropriately describe all classes of things and ideas. Some classes, like light, time, subatomic phenomenon and human nature, have more than one nature and therefore, cannot be correctly described by a single description. In going beyond the metaphysics of Plato, we also go beyond the logic of Aristotle, which is not reasonable in every case. Philosophy, psychology, and modern physics draw our attention to the fact that Plato’s theory of nature is no longer appropriate in all cases. And because our present system of logic is based on Plato’s theory, we need to question the validity of reasoning based on those laws of logic and the language in which we convey that reasoning. “It is incorrect to presume that any rational [Aristotilian] description will ever be able to reach ‘reality itself’”. (ZYGON Magazine, Vol. 25, No. 4, 1990)

In summary, as long as we are limited to Aristotle’s and Gautama’s judgmental rules of logic, we will too often be torn between what is morally wrong but rationally right.

I have demonstrated that the judgmental character of our reasoning comes from our laws of logic. Accepting this, we can imagine that it is not the reasoning mind, as a whole, which is to blame for the human condition. But rather, the judgmental reasoning, which dominates the civilized world with its judgmental rules of logic, is to blame. It is these rules, the only rules of logic we have—not the nature of the reasoning mind—which causes the disharmony between mind and spirit. It is also reasoning according to traditional rules of logic that makes the mind, according to Eastern thought, less reliable than spiritual discernment. From this we can conclude that additional nonjudgmental rules of logic, warranted by the principle that some classes have more than one nature, can expand the possibilities of the reasoning mind to mirror spiritual principles. And, in turn, these rules would empower the mind to be harmonious with spiritual values and capable of accurately describing reality and truth.

I offer new nonjudgmental rules for correct reasoning, which I call “nonjudgmental logic.” This logic supports oneness, limitlessness, and unconditional acceptance, or as some might call it, paradoxical, spiritual, heart felt, or quantum thinking. Let us now explore the potentials of this logic.