Learn more about The Practical Side of Heaven

Copyright William C. Kiefert. All Rights Reserved.

Chapter Two, Part Ten: Does Humanity Have More Than One Nature?

I will take time here to argue that humanity is a class that has more than one nature. It is important to do this because later we will see that Jesus used this same argument to justify nonjudgmental logic. The point is that Jesus’ system of nonjudgmental logic is based on the credibility that some classes—namely humanity—have more than one nature. This makes nonjudgmental logic not only desirable, but a logical necessity. Think about it. How could anyone prove that humanity has but one nature? Human nature is a subjective concept, not an object that can be analyzed.

Plato wrote in the Republic that “we are accustomed to posit a single form for each group of many things to which we give the same name.” This implies that human beings share a single nature. We want to challenge this assumption. Later we will see that this same challenge justifies Jesus’ logic teachings.

In The Sane Society, Erich Fromm points out that mankind is infinitely malleable: he can live free or slave, rich or starving, in peace or in war, exploiting or cooperating. “There is hardly a psychic state in which man cannot live, and hardly anything which cannot be done with him, or for which he cannot be used. All these considerations need to justify the assumption that there is no such thing as a nature common to all men . . . .”

Fromm has stated the obvious. For if there is one human nature, why then are people so different? Why is religion so important to some of us, and yet it plays an insignificant, even non-existent role in the lives of others? Why do some of us find science so thrilling to study, and others are completely uninterested in studying biology or physics, for example? As children, why did some of us want chemistry sets and begin to experiment at an early age, whereas others, even in high school, were unimpressed by the fact that water is made from one oxygen and two hydrogen atoms? Why do some of us hold such firm political convictions, and others of us are totally uninterested in politics? These questions would not be hard to answer if we accepted that humanity consisted of many human natures.

Years ago, C. P. Snow noted that two distinct “cultures” exist in our society: science, on the one hand, and the humanities, on the other. Snow lamented the fact that very often those of us in the sciences know and care little about the humanities, and those of us in humanities know and care little about the sciences. The fact is that the sciences and the humanities generally require an entirely different kind of mentality. That requirement suggests that humanity does consist of at least two human natures.

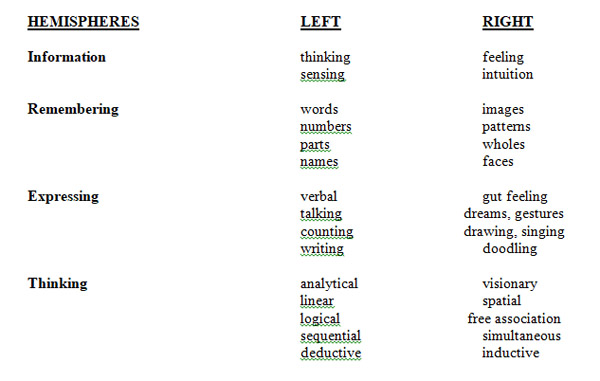

Researchers have found that the human brain has two distinct hemispheres each of which harbors different functions. Roger Sperry, Joseph Bogen, and Michael Gazzaniga have discovered in their research that it is as though there are two separate minds within a person. There are two quite different ways, then, in which we experience the world.

The left hemisphere is associated with language and speech, mathematics and verbal memory, and a sense of time: with the “verbal, analytic, reductive-into-parts, sequential, rational, time-oriented and discontinuous.” The right hemisphere, on the other hand, is associated with visual, tactile, and spatial organization, depth perception, and general patterns: with the “non-verbal, holistic, synthetic, visuo-spatial, intuitive, timeless and diffuse.” The brain, then, functions in two distinct ways, according to its two distinct, though connected, hemispheres or natures. In an unpublished paper, metaphysician Diana Beth Gaedig summarized the functions of these hemispheres as follows:

We tend to experience the world in one of two ways, according to which of the two hemispheres we are using. We think in different ways, depending upon which hemisphere is dominant. Studies by Jacob Getzels and Philip Jackson in the late Fifties indicated that there were two types of thinking: convergence and divergence. In convergence, which is associated with the left hemisphere, reasoning tends to be linear, vertical, and one-dimensional. This is the scientific temperament, which values the convergence on the stated problem to find the answer through logical, observational, experimental, and mathematical methods. In divergence, on the other hand, reasoning tends to be more creative, integrative, lateral, and multi-dimensional. Divergence involves the process whereby questions are originated and possibilities are imagined. Problems are not so much solved, as they are with convergers, as reformulated and elaborated; and new ideas are played with imaginatively through processes such as brainstorming or free association.

Depending upon which hemisphere is dominant for us, we will display different psychological natures or dispositions as well as preference for different disciplines. Those of us predisposed to divergence tend to gravitate toward English, history, the arts, philosophy, the social sciences, and modern languages. The intuitive, feeling, and insightful function of the consciousness is more dominant in these fields. On the other hand, those of us predisposed to convergence tend to prefer the hard sciences and the highly inflected or structured classical languages. The former often possess general knowledge; the latter, specialized information.

Edward De Bono draws a similar distinction; his terms are “lateral” and “vertical” thinking. By “vertical thinking” De Bono means reasoning from a paradigm or standard. What is considered a fact must fit the accepted schema. This is characteristic of thinking, which conforms to the accepted standard, whether the standard be scientific, religious, ethical, or political. Vertical thinking is “thinking on one plane.” It is limited by its passive tendency to attempt to fit everything into the established model or paradigm. A certain rigidity and conformity exists in vertical thinking. Lateral thinking, on the other hand, suspends these limiting structures and entertains the possibilities of alternatives.

In all fields, people differ. In science, there are those great scientists who make discoveries within the given paradigm, and there are those who alter the paradigm. Even in science, there are those scientists who are more willing to accept their own subjective judgment than are others of their colleagues. Einstein, for example, was so moved by the beauty of the simplicity of the mathematics, which he used to describe the universe, that he believed in its truth because of its beauty and simplicity. He accepted subjective criteria by which to assess the truth of his theories, rather than merely the objective criteria. This shows his trust in his own authority. He even remarked that if the universe didn’t fit his mathematics, so much worse for the universe!

In his Philosophical Investigations, Wittgenstein took issue with the idea that there was a single nature shared by all members of a class, which he likened to members of a family. There are obvious resemblances between children and parents; biologically, the children share the genes of their parents. But this does not mean that they necessarily share something more fundamental, some essence or nature in the Platonic or Aristotelian sense.

In music, some musicians play and compose within the given parameters; others extend them. Bach operated largely within the musical standards, whereas Beethoven broke with the standards of his day. We admire Picasso in art, Newton and Einstein in physics, and Darwin in biology, for going beyond the accepted frameworks of their day. Those who break with tradition, whether scientific or artistic, religious or economic, are operating from a different authority, often from their own subjective authority. But it takes a certain nature or temperament to do this. Some of us have it; others do not. Even here, we are by nature essentially different.

Psychologist Carl Jung distinguished four functions which differ in their strength and prominence in people. “I have found from experience that the basic psychological functions… prove to be thinking, feeling, sensation, and intuition. If one of these functions habitually predominates, a corresponding type results.”

Jung represents modern psychology’s tendency to divide human nature into four distinct types. Ancient writers did the same. Plato, in the Third Book of his Republic (414B-417B), suggested that citizens be told the fiction that different metals ran in their veins, making them different. Plato followed Hesiod’s lead in choosing gold, silver, bronze, and iron. The ancient Greek physician, Galen, proposed dividing human beings into four types according to the predominant “humors” or psychological natures: melancholic, phlegmatic, sanguine, and choleric. Behaviorist H. J. Eysenck divides human beings into four types, according to whether they are predominantly introverts or extroverts. The Briggs-Myers personality tests make similar four-fold classifications. It is not necessary, however, to accept any particular way of dividing human beings into types or natures in order to accept the fact that humanity consists of many human natures.